Michael Livingston’s Origins of the Wheel of Time is a deep dive into all things Robert Jordan: the man, the myths he used to craft his legendary series, and a final, lingering look behind the pages that have moved so many readers over the years. It’s also immensely readable, appealing to both hardcore fans and more casual series readers alike.

I’d count myself in the former category, and when reviewing a companion work I think it’s important to provide the reviewer’s frame of reference so the reader can take that into account when considering clicking the buy link at the end. So let me come clean. I started on The Great Hunt as a teenager (because back in the day, the local bookstore didn’t have every volume), devoured the series (eventually looping back to The Eye of the World), got to meet Robert Jordan on his final Knife of Dreams tour, refreshed his blog every day to see if he’d posted yet when he was fighting for his life, was eviscerated at his passing, went to every Sanderson tour, became a writer in part because of Jordan, workshopped my debut with Sanderson on a Writing Excuses Retreat because he finished the series I loved, and chose Tor as a home for my own series because it was where Jordan came from. I’ve read the series nine times (save for A Memory of Light) and I’ve written numerous essays for Tor.com on Randland. But I didn’t go full Criminal Minds on who killed Asmodean, take up my keyboard in forum flame wars, and I haven’t written a dozen pages on how Rand lit that damned pipe. More importantly, I have a number of friends who enjoy Jordan, but aren’t enamored of him. So while I am more than just a casual fan, I think I can give you a fair perspective on what you’ll find in Origins.

The truth is I didn’t expect Livingston to unearth anything I didn’t already know and I was pleasantly surprised to discover I was mistaken. Badly, in fact. There’s a wonderful foreward from Jordan’s wife Harriet followed by a note from Livingston explaining how he came to The Wheel of Time as a fan and then a writer for this project and a lengthy intro. All of these will appeal to the reader who wishes they had just one more peek behind the curtain at the key players behind the creation of this series. Of course they aren’t players, but real, living, breathing, people. People who moved in the orbit that was Robert Jordan and having had the chance to meet him briefly, I can attest that he was a character in the best sense of the word.

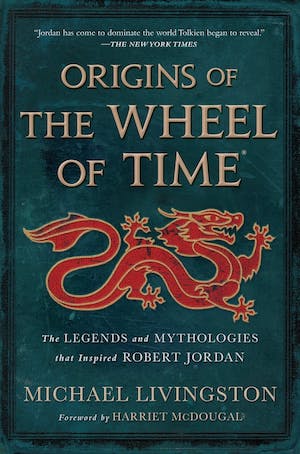

Buy the Book

Origins of the The Wheel of Time

Origins is broken down into several parts. It’s the story of the Maker and the Making. Beginning with vignettes of Jordan’s life, we get to see what made him the author that came later. This was one of my favorite parts, because I love origin stories, and while I knew the story of Jordan’s brother teaching him to read at age three, I didn’t know that led to some trouble for him later on. He was kicked out of Sunday school for his precociousness, he got along so well in grade school that he never learned how to study and this caused him to wash out of college after his freshman year and land in Vietnam hanging out the door of a Huey behind a pig (an M60) for two combat tours. Livingston fills in the blanks from Vietnam to Jordan’s walking away from a career in nuclear engineering to try his hand as a writer and it’s this blend of familiar stories with new, moving ones long hidden from view that I found so satisfying. They’re not enough, friends, not by half, but if they left me wanting to know more, I was at least glad at what I had learned.

The making of Randland is the second, and largest part of the book and here is where Livingston’s formal training as a professor of history really shines. He dissects Jordan’s personal notes to reveal the three pillars of literature Jordan used to craft his own epic. One of them I wasn’t surprised by (Le Morte d’Arthur by Sir Thomas Malory), one I’d never heard of (The White Goddess by Robert Graves), and one of those we’ve always known: Tolkien. The Arthurian mythos is one Jordan made clear, especially in early books while Graves’ work is more fiction than fact that tries to create a European ur-mythos that ties back to a three-faced moon goddess, but unsurprisingly, Tolkien seems to have had the greatest influence. Livingston makes a convincing case that while Jordan drew from a similar background of philological and mythological history like Tolkien, Jordan was able to leverage the diversity of America and draw from every culture in the world. While Jordan admitted to some of this iceberg lurking beneath the waters of the Aryth Ocean in interviews and other pieces were guessed at on forums across the net, this is the first definitive discussion using the man’s own words and thoughts as support. Importantly, we get glimpses into where Jordan deliberately left the paths of the other works he was using as a foundation to create something wholly novel. Watching the evolution of Jordan’s ideas over the course of decades is fascinating and will give insight for readers who wonder how writers create something from nothing and provide fodder for writers interested in the craft behind the words.

I was glad to see that Livingston doesn’t shy away from some of the “rougher” edges of Randland. He digs into some of the binary setups of the world, providing context on why Jordan chose them, what was intentionally binary and what was not addressed, but assumed to be binary. The necessary conversations we’re having today about gender and identity weren’t happening broadly in the same way when Jordan was alive, so nothing definitive is asserted, but I will say it gave me a lot to ponder there. That’s likely a whole essay in and of itself. Another point of contention–Rand’s multi-love triangle (quadrangle?)–ties directly into some core mythos from our own world that Jordan was drawing upon. It was refreshing to learn that the setup wasn’t just to make Rand out to be, in Rand’s own words, “a lecher, or just a greedy fool”.

Throughout the book, I was struck by just how many references to our own world Jordan included, in ways both large and small. They truly are legion. So it’s fitting that the book concludes with a detailed index of names, places, concepts, etc. and where ties to our own world were found in Jordan’s notes. This is the portion of the book that may be for the diehard fans, but it’s not required reading and I suspect it would be handy when doing a reread to have it close to hand to flip to a specific place if something catches the eye. For map lovers, the correction–after three decades–of the world map may be worth the price of admission alone.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t touch on a few hot button topics for series fans…yes as advertised there is some more revealed about Nakomi and Rand’s damned pipe. We learn what other series and outrigger novels–as Robert Jordan called them–might have been. There’s a line about Perrin that gave me chills and set my mind to racing. So, should you pick this up? If you’ve spent time on the page, walked side by side with Nynaeve and Egwene, Elayne and Aviendha, Min and Mat, Thom and Moraine, Perrin and Rand, then I don’t think you’ll be disappointed. At the least, you’ll feel that old familiar wind rising, brushing past your cheek, leaving you forever changed.

One last time.

Origins of the Wheel of Time is published by Tor Books

Read a series of essays from the author Michael Livingston

Ryan Van Loan served six years in the U.S. Army Infantry, on the front lines of Afghanistan. He now works in healthcare innovation. His debut novel was The Sin in the Steel, the first volume in The Fall of the Gods series; it was followed by The Justice in Revenge and The Memory in the Blood. Van Loan and his wife live in Pennsylvania.

I have never yet dipped into the Magnus Opus of Mr Jordan and, one must admit, seeing Mr Robert Graves’ WHITE GODDESS mentioned as one of it’s key influences gives me the jitters – I admire the gentleman’s novels, but reading his THE GREEK MYTHS left me equally gun-shy about reading his ‘GODDESS’ (because while his compilation of Classical Mythologies greatest hits is extremely useful, his theories on their ‘true’ origins have the worryingly earnest monomania of a Conspiracy Theorist).

Omg! Someone else who actually read TGH first!

I pre-ordered the book and started reading as soon as it was delivered. The two lines from Jordan’s notes about the proposed Seanchan series were indeed chills inducing!

I thoroughly enjoyed this book, it rightfully has a place next to The Wheel of Time Companion and The Complete World of the Wheel of Time. My review: I thought this was fascinating and a very valid addition to my “books about the Wheel of Time” collection. The author (true fan) has access to the very inner circle of WoT materials and personalities, including Jordan’s own notes, and has created an inside look at the inspirations and creation of the seminal fantasy series. Plus it was well written, fun and engaging.

We see Jordon’s upbringing and background, his personal fandoms, his brainstorming, his muses both human and literary. Parts I found particularly facinating are the glimpses into his thought patterns and the path from what he thought the story might be to where it ended up. Also there is a section on the inspirations for allllll those names, covering basically all of myth and legend from a very heavy Arthurian angle to Persian, Irish/Celtic, Greek, Welsh, Romany, Christianity, Muslim, Buddism, on and on, so much depth and breadth! And I am totally kicking myself for not making the connection between Tarman Gai’dan and Armageddon. DOH.

My only complaints are the places where the author guessed the name connections (not many, but I want TRUEFACTS) and the big font and large margins. There is no shame in a small book, especially not one as packed with goodness as this one. Save a tree, people!

Graves’ “White Goddess” is the moon, along with female gods who he believed represented the moon in ancient European religions. Graves is not taken terribly seriously by anthropologists, but his ideas are intriguing.